The Morally Correct Way to Grieve

Life keeps forcing cruel choices.

I. A Question on My Mind

Without too much difficulty, we can all probably conjure an example of the wrong way to suffer the loss of something important. The worst of this is often triggered by the cost of a loved one.

Recently I have found myself in many unintentional encounters with movies, television, books, and games driven by stories of those who are grieving something incalculable (editor note: while I don’t address it in this piece, I recently read the book Blood Over Bright Haven. It’s a riveting example). Grief so massive, endless, and impossible that it crushes the soul and warps those hurting inside it, until they are unrecognizable even to themselves.

Without spoilers, this is the central conceit of the horror film ‘Bring Her Back’ the central antagonist of which is a black hole of suffering so all-consuming that it would destroy anyone and everyone who gets in their way. Not out of malice, but because there’s no other conceivable option. Their world has become this one thing, to the detriment of all else.

Pain that big is rarely understood. Engaging with it requires nuance, extraordinary compassion, and a willingness to potentially be hurt by the hurting person. When people are caught up in the tides of that loss, without the ability or tools to adequately cope with it, it’s inevitable that such pain will ripple out beyond themselves.

But I don’t want to talk about Bring Her Back, even if it does have my favorite movie character of this year. I was drawn to the intersection of morality and grief due to something else entirely.

The monumental hit “Clair Obscur: Expedition 33” by Sandfall Interactive is a game whose abiding ethos is to not go gently into that good night. Echoes of inevitable endings ring throughout the halls of its narrative, in blood-soaked declarations of “When one falls, we continue” and “For those who come after.”

It is a phenomenal title, glowing with the passion and craft of people who wanted to make something beautiful, but devastating. They may have accidentally created the game of the decade, and will certainly walk away with Game of the Year, if online discourse is to be believed. But I am not here to sing the praises about the game. You can find others who have already done that, many more eloquently than myself.

I am, however, going to insist that you finish Expedition 33 before we continue, because while I will speak vaguely of the ending, I do need to add enough clarity for my points to be coherent which will mean a degree of spoilers. And this is not a game that you should go into with major story beats ruined in advance.

That said, this article is not about the ending. It’s about how fans have responded to it, and the ethical fissure it has made amongst them. The reactions fans have had toward the ending has become one of the most divisive and memorable in the video game landscape. An ending so well-wrought that I am forced to believe it was used as the core by which everything else was scaffolding.

I must make one final plea: if you are at all interested in playing Expedition 33, or have any loyalty to the turn-based genre, or simply enjoy an uncommonly stellar narrative, please disregard the rest of this writing until you’ve had a chance to play the game to completion. I have gone back and forth one whether or not to write this at all, knowing some of my friends will read it for whom I do not want to spoil the experience. Rarely do I feel this protective of a story and its secrets. It behooves me to take all precautions against tarnishing that.

Because at the heart of Expedition 33 lies a question that I’ve witnessed enflame an already passionate community. And for that, I cannot hide our subject overly so in ambiguity.

We all know there is a morally wrong way to grieve. History is riddled in examples.

But is there a morally correct one?

II. Fiction Vs. Creation

If you are to play through Clair Obscur: Expedition 33’s story in its entirety, you will roll credits with a very strong opinion about the nature of the world you are in and the people who fill its lands. What you think of them will ultimately inform which side you took during the final battle.

Were they actually real people, with hopes, dreams, histories, and homes?

Or are they false souls: very detailed, nearly perfect simulacrums?

Their world was created by gods, ones that we become familiar with over the course of the game. Gods who are mortal, and fallible, and incomplete. What does that make Gustave and Lune and Sciel and all of them, to be crafted by the minds of imperfect deities?

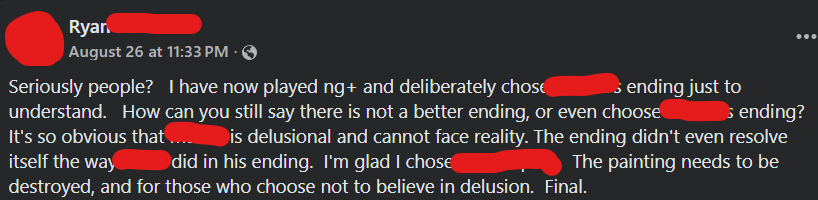

If you ask the fans, you get two very different, very heated answers. If you chose the “wrong” one (there’s not a wrong one, more on that later) you will be lambasted and the integrity of your character brought into question.

Take one side and you condone genocide. How rude of you. Take the other side, and you’re complicit in perpetuating a child’s delusion and denying a family its chance to heal. Either way, wow, you suck. You should feel bad about yourself. Go find Jesus.

An important aside: if you’re not aware, video games have a long history of allowing players to obtain multiple endings. It is one of the most unique features of video games as a medium. Most other media does not have this ability, save for a few fringe examples, but in games, it’s commonplace. What’s more, there is a deeply ingrained notion that there is almost always a “good” or “true” ending and one or more “bad” endings. Which, to be clear, is almost universally true. Most games do draw clear lines like that, and have for decades.

However, that creates a problem for Expedition 33. Because I am of the firm opinion that the developers had no intentions to create such clear designations, and I know I’m not alone in that. From the outset, E33 is a genre tragedy. By design, there was never going to be a happy ending. Or rather, there is one, but the characters are too broken and dysfunctional to reach it.

But because this is such a tradition in games, you now have hundreds of thousands of players who insist their choice is the “good” and “true” ending intended by the developers, regardless of which ending that is. Thus, tribalism ensues. Two tribes born of one ultimate question, which circles us back to my earlier point: are these people real, or are they not? Everything hinges on that.

Ultimately your opinion on the ending boils down to whether you believe the people of the Canvas are advanced works of fiction, or living creations. They were created, yes, that is indisputable. But the nature of that creation is where the question lies.

For if they are truly, completely real—creations of gods, living not in a false reality, but a pocket reality just as real as any other—then you cannot take the side that involves their mass, permanent extermination. You can’t. It’s morally reprehensible. Even if you know that this way will also lead to suffering, you cannot bring yourself to kill that much life, not when you have the power to save them all.

And if they are fiction—functionally nothing more than super-advanced, very convincing daydreams created by a grieving mother—then who cares if they die? They aren’t real. They are imaginary friends, and continuing to indulge in the safety of their comfort is irresponsible. You are preventing a family from healing. (This assumes that in this ending, healing would actually happen, which is a tall assumption considering everything else we know about the characters involved).

So much hinges upon the answer, of course it could not be spoken of gently. And for those who finished the game, few have been gentle, indeed.

III. The Grief of It All

Everything I just said is complicated further by the wrinkle that, because this is a narrative-centric story, it’s not just you as the player making the aforementioned decision, but two of the characters, as well. Each of them know the implications of the problem and its (perceived) binary of solutions, and are acting on their own grieving self-interest, and what they believe is the best decision for the most people.

One of them is a god. The other, a creation. They are sister and brother.

In one corner: a girl who hates herself and her life beyond the Canvas world. It is a place in which she has no friends, feels very little love from most of her family, and experiences open disdain from the rest. In her youthful naivete, she made a decision that cost the life of a family member, and everyone knows it is her fault. What’s more, she is maimed, in perpetual pain from third-degree burns, and is trapped in a pre-designed future she does not want.

In choosing to side with her, you allow the created world to persist, the one she has called home for 16 years. A place where she has the power to not only live without pain, but help others live without pain, as well. She could earnestly give a broken world the hope it has craved for generations. It would simply cost her soul, and potentially result in the decimation of her personality, as well-meaning as she is. It would also mean forcing a young, tired boy to work without ceasing, an unpleasant requirement to continue maintaining the world they are in. As long as he does not rest, ever, the people of the Canvas may go on, as well as her hope for the future.

The other corner holds a man who both died too young, yet has lived too long. A knowing, conscious entity, aware of his existence as a copy of a dead man, a brother lost in the same fire that disfigured the girl. He is their mother’s desperation: a living, unkillable ghost that exists only because a god could not tolerate a world without her son in it. And so, he wants to die. Of course he does. Cursed with his involuntary immortality, he is doomed to suffer through the deaths of thousands of others, unable to meaningfully make a difference. His only hope for release is to make a young, tired boy stop holding the world together, and thus allow it to finally dissolve. His god-sister would be released into the life she hates, and the people of the Canvas would fade into nothing. This is not something he wants. But it is the only hope he has for both himself, and the family beyond the Canvas to come to terms with his passing.

The end of this game is a battle of whose grief is stronger: which is more desperate to avoid their worst possible outcome, their worst possible life? Both of them would rather die, than continue living in a world that has doomed them.

No happy endings. Only the pain and fear of losing even more, when everything else is already lost.

Which would you choose? Whose pain do you understand more? Which of these characters will you doom to anguish, with all the other ramifications that anguish may entail (we have no reason to believe, for example, that if expelled from the Canvas, the girl would not take her life. She despairs that much. To assume she and her family must heal and move on is extremely optimistic).

What is the morally correct way to grieve?

This question was always hypothetical, but you probably knew that. I have no credentials or experience that deems me worthy to answer it.

I wrote this entire piece mostly to fight back against the overly simplified discourse that comes in the wake of the outlined decision. Because, tragically, if you spend too much time reading opinions about this choice as I have, the waves of reductive, ill-equipped logic will leave you discouraged.

The man is condemned as a fool, a liar, a traitor. The game asked for you to empathize with him, and the people of the Canvas. How dare he lie to you, use you and the girl to reach his ends? Fuck him, right? Fuck him for not wanting to suffer forever. Fuck his sadness and his pain.

The girl’s condemnation is a bit more complicated. The more generous among her scorners blame her short-sightedness on her youth. She is, after all, a child (sort of? She did live to be 16 twice. But that doesn’t really make her 32, does it?). Others are less kind. Her desire to maintain this ideal reality at any cost (even resurrecting the dead) is proof of her narcissism. She’s cruel, sociopathic, vengeful. Fuck her for being too young and too scared to make the wisest decision out of losing options.

To quote a father: “Life keeps forcing cruel choices.”

The developers of Expedition 33 know how miserable this situation is, they did it on purpose. This is why I don’t buy any narrative that spins one rationale as inherently more correct than the other. This was supposed to be hard to choose, and if it wasn’t, then there’s a high likelihood that you did not come away from this game seeing the characters as intended. If they weren’t real that whole time, then shit, this was easy. The man is objectively correct. But that wouldn’t be a cruel or difficult choice, which flies in the face of a central tenet of the game. If the decision is easy, then either the game didn’t do a good job of establishing its principles and purpose, or you simply didn’t absorb the message.

Which should not be a source of shame. It’s an opportunity to revisit the story with a fresh lens (and boy howdy, playing this game a second time with all the end-game context is illuminating).

There is not a morally correct way to grieve. But we must meet one another in the grieving. I know its trendy in some circles to demonize empathy these days. I know it’s a lot of work. Not everyone wants to perform critical, emotional and mental legwork when they sit down to play a game. But if you don’t, then you get caught on one side of a fence that shouldn’t exist.

The girl’s grieving is flawed, because she is flawed. The man’s grieving is flawed, because he is flawed. They are broken people stuck in a cruel situation, forced to make cruel choices. In a perfect world, neither of them would wish anything ill on anybody else. We have spent time with them. We know of their kindness. We want them to be happy.

If that’s impossible, then we must do the next best thing: In lieu of being unable to make that choice in their place, we must find it in ourselves to have mercy on their imperfections.

Clair Obscur activates two conflicting frameworks for understanding its world at once, which is what makes it so painful. You see the pain that each character brings to their choices, and see how it warps them in a unique way. And it breaks your heart.